(You get a bonus cookie made of dust and the tears of fairies if you listen to this all the way through.

Tuesday, 28 June 2016

Sunday, 26 June 2016

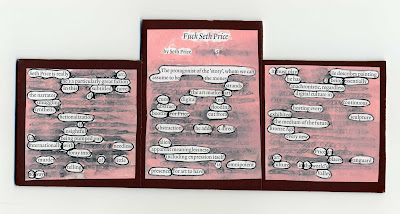

Art Review Review Triptych (for Seth Price)

Labels:

art,

art review,

collage review,

conceptual art,

erasure poem,

poetry,

review,

seth price,

triptych

Friday, 24 June 2016

George Ttoouli says, “Because: No.” (Or, Why Ecopoetics?) (5/5)

I'm trying to adapt from high modernist elitism here, to how we are morally expected to respond to impending climatic changes and catastrophes. The critic shouldn't demand we elevate ourselves to the level of the poem; instead, poetry demands we elevate ourselves to the level of the crisis we're living through. Literature is a training ground for citizenship, be that an environmentally activist citizenry, or a capitalist citizenry; the poetry isn't good or bad inherently, until we bring in our readerly values to appraise it. Shoptaw's essay shows an assimilation of certain key nodes, but effectively retains control by adopting a hieratic, hierarchical authoritative, gate-keeper role over which poems will pass through into his ivy-clad ivory tower.

Thematic change does not equal structural change and I've been invested in thinking about the latter for a while. OK, I admit I've a bugbear to bash just after I'm done grinding this axe. Poetry invites a better world by inviting people to think differently about their role in the world. On the other hand, if people begin to think and read and live better than some poetry allows, is capable of (as Shoptaw has done), then, regardless, the world gets better. We could learn to read, for ourselves, the ecological thinking at work in any poem, any government broadcast, any corporate advertising campaign, and decide for ourselves which path to follow.

Obviously I'm on the side of poets and editors and thinkers who argue against the formation of ecopoetry as a category (well argued, I feel, by Harriet Tarlo, when I once heard her speak about The GroundAslant: Radical Landscape Poetry [4]). It's unnecessary; it's business as usual. A similar thing happened with slipstream fiction, according to China Miéville: at a certain point, it simply lost the energy of its initial formation as an intellectual provocation, a realigning of certain boundaries and traditions. These things have a sell-by-date, in other words; and (contra to Miéville), I'd go so far as to say the whole premise of genre-definition is a rotten enterprise, serving not readers, but profit, creating and reinforcing an elite power base.

Ask instead what underlies the poetics, the processes, even the publishing mechanisms by which a poem lands on your lap or in your inbox. Ask yourself if, given the fact of our planet rumbling toward a hot hell in its greasy handcart, we should start reading poetry differently, asking what it is in those older nature poems that shows how we should have been thinking differently about our relationship to our home planet. And what if we start reading poetry afresh now, start examining our current cultural producers through these eyes?

Ashbery's poetry, as much as Cunningham's or Spahr's, offers a broad range of engagements for thinking about the world. And these poems might also be called humorous, or political; poems of life and death, of place and experience; they're all love poems, love of each other, love of cohabitants on the earth, and love of habitat. All these categories publishers and academics and students and readers and people have at their disposal for talking about a poem they've read: to what end? I don't want or need yet another straitjacket for how to read a poem, but I'm happy to expand the tools available to me for reading and enjoying poetry.

*

That's it, it's done, well done, you've earned enough karma to kick a deer to death. Maybe even two.

---

*

That's it, it's done, well done, you've earned enough karma to kick a deer to death. Maybe even two.

---

[4] Although, even that title has to try and justify the anthology's purpose by categorising loosely. I like that 'radical landscape poetry' is so clunky as to never catch on as a publishing buzzword/genre. See discussion about slipstream for a counter – therein, maybe, is a solution: call it 'contemporary ecologically-conscious poetry' and no one will bother genrifying it for market purposes.

Labels:

because no,

ecopoetics,

Essays,

John Shoptaw,

nature writing

Thursday, 23 June 2016

George Ttoouli says, “Because: No.” (Or, Why Ecopoetics?) (4/5)

Another example of the problems in Shoptaw's taxonomic approach emerges in his reading of Brent Cunningham's 'Bird & Forest.' He criticises the echoes in Cunningham's line about how the bird “doesn't think, but uses the machine of instinct buried in its flesh, a device wrapped in an assembly.”

For Shoptaw, the word “machine” invokes Descartes' description of animals as “mere animated automatons, devoid of thought or emotion.” So the essay argues against an anthropocentric stance in Cunningham's poem, which “soars above vulgar reality into postmodern pastiche.” Initially I'm in agreement with Shoptaw's stance, which takes against Descartes, and, thereby indirectly, the hierarchical, anthropocentric divisions between animal and human.

But can 'Bird & Forest' be both postmodern pastiche and grounded in early modern philosophy, without demonstrating some criticality about Descartes? (No, obvs.) The line about the bird as 'machine' and 'assembly' should trigger the nervous tic of anyone who's read Deleuze and Guattari. Shoptaw has overlooked the contemporary philosophical vocabulary referenced by Cunningham's piece, which is very likely a better channel for reading the line.

Taken through D&G's philosophical readings of material experience, their refutation of binary, or Cartesian, logic, their postmodern approach to reading all 'nature' not as a series of discrete boxes, but as a continuous series of processual becomings and imbrications (plateaus, planes of immanence, assemblages, machines, and so on), Cunningham's poem evokes a very different sense of the bird and the forest in those lines. That's a long sentence, I know, but I prefer to condense D&G into near-meaningless sound bites because it gets funny reactions from D&G scholars.

My reading of the poem through D&G, and critique of taxonomic philosophical approaches, bears out if you return to the extract from 'Bird & Forest' included in The Arcadia Project. It's a far more complex work than the two lines Shoptaw quotes. Those two lines are even taken from two separate sections in a poem with several parts, the last several of which are all notes to the first two (called, respectively, PRINCIPLE OF THE FOREST and PRINCIPLE OF THE BIRD). As the poem offers in Note 10:

I began by writing anything, in any order, as awkwardly as it could be, at any time. And I discovered, as I wanted to, a method. Not a perfected one, but one day…................Language doesn't become strange by torturing it. It becomes strange by giving it a task too simple to complete. Look at the poor thing, pressed by the illogics of being, trying to fly between some clearing and other.

Cunningham's poem addresses at least some of the philosophical methodologies underpinning how to read nature, by which we describe something as 'bird' and another thing as 'thought.' Through D&G, or (perhaps more accessibly) recent material ecocriticism, eco-thinkers have begun to consider not just the material qualities of language – the subjectile qualities of pen, paper, ink, the toxicity of production processes, the energy that goes into making a book – but also the material qualities of thought: the neurons that fire off in delight when you see a bird flying through branches and the contrast of light and shadow in a forest; the way we have constructed a series of material, natural-based metaphors for flights of fancy and trains of thinking, or twittering for social interactions, to ground the line from matter to mental processes. What about the ideological frames through which we relate to the world? Material processes drive thought, what happens when we think of thought as matter?

Underpinning 'Bird & Forest' is an interrogation of rational philosophical processes, a challenge to the idea of an axiomatic, human-centric, non-messy, dematerialised understanding of the real world and how we relate to it. How self and world co-produce each other, even as we pretend otherwise. How this pretence filters out into ecological damage.

Perhaps the poem isn't explicit enough for Shoptaw's argument; perhaps it allows me to reach a similar point of ecological thinking as that allowed by Juliana Spahr's poem, but by other means, because of my particular training, thinking, development; because of my ecopoetics. Perhaps, more importantly, the taxonomic approach ignores the structural environmental politics because it does not require the reader elevate to the level of current ecological thinking necessitated by climate change, instead bogging itself down in mere content, subject matter, themes.

*

Last part tomorrow, you're a trooper!

Last part tomorrow, you're a trooper!

Labels:

because no,

ecopoetics,

Essays,

John Shoptaw,

nature writing

Wednesday, 22 June 2016

George Ttoouli says, “Because: No.” (Or, Why Ecopoetics?) (3/5)

GT does go on some, doesn't he? He's still responding to John Shoptaw's essay...

Yes, some poetry is more rewarding, according to personal tastes. Some poems offer a better sense than others, of the key challenges we face today as a species: climate, culture, ecology, the whole sociopolitical shebang. I disagree with the fundamental principle that says the 'better' poems require a whole new category, marked 'ecopoetry,' to distinguish them from earlier, now-redundant 'nature poetry.' Shoptaw is building a wall and I want to know why he wants to keep a certain kind of poetry out: cui bono? All of it says something about our relationship to the planet, even one of Fred Seidel's love poems to a motorcycle.

Yes, some poetry is more rewarding, according to personal tastes. Some poems offer a better sense than others, of the key challenges we face today as a species: climate, culture, ecology, the whole sociopolitical shebang. I disagree with the fundamental principle that says the 'better' poems require a whole new category, marked 'ecopoetry,' to distinguish them from earlier, now-redundant 'nature poetry.' Shoptaw is building a wall and I want to know why he wants to keep a certain kind of poetry out: cui bono? All of it says something about our relationship to the planet, even one of Fred Seidel's love poems to a motorcycle.

Time and again I've found the motivation for grounding new genre categories in literature, as with any technological advance, serves to stake out market territory and gain power and profit (or both, as today's cultural norm has it). G&P co-editor ST has often bemoaned my reaction to markets and commercialism as a knee-jerk analysis. So I'll not go too far into a speculative rant about Shoptaw's motives, biases; there is a fundamental problem in the imbroglio of capital and intellect, humanism and pornography, which I feel should be tackled head on in articles that descend into the quaggy depths of taxonomising.

Instead I'll focus on the structural problem Shoptaw raises in attempting to define a genre. Let's ask again: What is ecopoetry? Shoptaw states: “an ecopoem needs to be environmental and it needs to be environmentalist”.

Where I come from, 'enviromental' is olde worlde ecologic, theoretically unpicked for its Cartesian separation of nature and culture, human and animal, inside and outside. Recent critics, such as Timothy Morton (Ecology without Nature), have quite substantially argued against the idea of a separation between nature and us: there is no standpoint, no imaginary position 'outside' of nature, from which we can objectively view and understand what nature is. DonnaHaraway calls what we live in 'naturecultures', to demonstrate the yin-yang mess of our own posthuman statuses.

We are not pure humans: we are bacteria-carrying, symbiotic messes, both dwellers and dwellings, always cohabitants in shared space. We can't hold up an 'environment' like an imaginary truth, to study it objectively, from afar. Throw Bill McKibben's The End of Nature into the mix, and you realise the idea of a pristine, wild nature is also a fantasy; the anthropocene is here, and it is both us, and is killing us, which is also a kind of slow motion suicide leap into a burning lake of oil.[2]

There is no spot on the planet untouched by the atmospheric changes caused by human activity; even if you want to argue the insignificance of these changes in some geographies, you have to accept that nature and culture (by which term, too often, we interpret an exclusively human culture) are utterly, inextricably imbricated, in a messy, mutual process of co-production. Just as the 'natural' existence of certain resources might drive human activity to follow, or focus on, particular geographical locations on the planet, allow for a variety of settlements and situations to arise in 'human cultures', so too we have chosen to remake the places we dwell in according to our own visions, landscaping lawns and putting in infrastructures for the transportation of food, energy and labour. (I'm drawing on Jason W. Moore's work; see for example Capitalism in the Web of Life, which distils his work into one handy book-for-the-uninitiated.)

At this point, a brief pause: I'm ranting about research I've done, time invested and possibly you know it all already. John Shoptaw probably knows all this already; but, maybe not, maybe this is a helpful reading list, a way of thinking how, when you next go to mow the lawn, or water a flower pot, you might think how natural selection of certain grasses, certain prettier flowers over others we might call weeds, is a human process. We are natural selectors. (Think: Michael Pollan's Botany of Desire, or his TED talk on what the lawn wants.)

Ask yourself: did you write that poem about that nightingale singing because there's something (the muse!) in you that decided that was what you needed, or did the nightingale learn to sing just like that to mess with your head? If we could translate the nightingale's song, wouldn't it really just be unspooling a tickertape of pornography about how big its sexual organs are and, Come get some, luvvrrrbrrrrds!

I'd completely side with Shoptaw on his disagreement with Morton's reading of Bernstein's poem. Bernstein's piece is just having a larf, as they say, and that's OK. No amount of excessive critical analysis can do away with the fact that it's an amuse bouche, so why spend so much energy on this, rather than one of Bernstein's more substantial offerings?

But let's not devalue Morton's right to choose to display his ecocritical perspective where he so wishes. That in itself is the point: you can read a depth of relevant, ecological thinking, into just about anything, and why not? Morton's attention to how a material space is constructed by the poem demonstrates a particularly expansive (ha-ha!) capacity for ecopoetics. Shoptaw's rejection of this in favour of taxonomising ecopoems suggests critical closure, an attempt to control discourse.

Instead of Morton, let's draw on some recent thinking in material ecocriticism (see Iovino and Oppermann's edited book of that title). Naturecultures can (should!) be thought of as collections of imbricated spectra and relations. Note the plural: there's more than one way to gut a (canoe)fish, or read/write ('wread' sayeth Jed Rasula in This Compost [3]) about the world.

We might separate between things that are more man-made than not, we might attempt to invent a language for the non-human, or extra-human (see, e.g. Les Murray's 'Bats Ultrasound' which captures a piece of bat-prayer in recorded ultrasound, really an attempt to empathise within the language of bats). But you ignore the natural elements informing even the most man-made built environment at your own risk, as much as vice versa, particularly in the fraught realms of current ecological destruction. That cobweb in the corner of the room might be holding the building up.

*

Srsly, you've read this far, just tune in again tomorrow.

---

Srsly, you've read this far, just tune in again tomorrow.

---

[2] Reading this book gave me nightmares. I once failed to remember the title, some months after reading it because I had repressed it, so overwhelmingly depressing it was. And I read the revised edition, where, in the intervening space of 20 years, humanity had done nothing to slow down carbon emissions or fossil fuel dependency – in fact had increased usage exponentially – and McKibben noted the irrational failure of our species to curb its oil addiction. Hence, now, I feel the metaphor is apt: a slow-motion suicide leap; inevitable now. Get used to hopelessness, there's only planning for collapse left to us. (Also, have you changed the oil in your car recently?)

[3] This one's a little more esoteric. I treat it as poetry, of sorts, something to be enjoyed for its language, for its play, as much as the ideas it infers.

Labels:

because no,

ecopoetics,

Essays,

John Shoptaw,

nature writing

Tuesday, 21 June 2016

George Ttoouli says, “Because: No.” (Or, Why Ecopoetics?) (2/5)

GT responding to John Shoptaw's essay.

Take Shoptaw's analysis of an Ashbery poem. The reading is, at first glance, open, engaging and, by bringing in Forrest Gander's Redstart, provides a waypoint for thinking about contemporary US ecopoetics. Shoptaw uses Ashbery's poem to establish differences between 'ecopoem' and 'nature poem,' and 'environmental' and 'environmentalism,' setting up his good/bad dichotomies.

Take Shoptaw's analysis of an Ashbery poem. The reading is, at first glance, open, engaging and, by bringing in Forrest Gander's Redstart, provides a waypoint for thinking about contemporary US ecopoetics. Shoptaw uses Ashbery's poem to establish differences between 'ecopoem' and 'nature poem,' and 'environmental' and 'environmentalism,' setting up his good/bad dichotomies.

The taxonomising underlying the approach, however, is a fundamentally un-ecopoetic method. The urge to define, box, distinguish, means the categories falsely and crudely set up boundaries where there are none. For a poem exploring the problems of sexual taxonomy, the parallel problems emerging in the article's attempts to box up ecopoetry are unavoidably ironic.

For every example Shoptaw provides for why Ashbery's poem isn't an ecopoem, the same text offers counters which trouble the nuances between ecopoetry and nature poetry. In reading Ashbery's use of erotic language in 'River of the Canoefish' Shoptaw concludes, “Ashbery’s culture poem is still fine and fun. But in my terms it can’t count as an ecopoem.” However, in the first line quoted in the essay – “These wilds came naturally by their monicker” – the poem constructs an ideological ground in which gay culture and wild, uncivilised naturecultures are mutually condemned by a dominant ideological position.[1] And, if you want to take Bill McKibben or similar into account, we're a part of nature; our culture, all taxonomies of human culture, are natural phenomena. Anything less than taking it as such, calling one culture 'unnatural', or whatever else, is tantamount to an ideological position of elitism.

Through transposition (metonymy rather than metaphor, or association by cohabitation, perhaps) to the wilds, the poem introduces a longevity to homosexuality in North America and indirectly offers a counter to homophobia, or worse, the sense that there have always been 'wilds' (gays) and 'tames' - ideological opposition to variations of sexuality.

These imaginary fish are an imposition, albeit likely a self-imposition in some cases, on gay identities, hence a construct. So too the idea of 'wilderness', wilds: the idea that a bunch of trees in a national park might self-identify as wild is ridiculous, unnecessary to the sense of self a tree might have. These imaginaries are related to, informed by, subjective versions of material experience, just as ideas about nature are constructed, some supposedly 'better' than others. The poem invites readers to think about where this nomenclature comes from and, if you want to follow that logic, invites you to think about the power of naming.

The question of how we value nature, the relationships we affirm, are reflected in how Ashbery's poem appraises different responses to homosexuality. That the Canoefish are “generally immune to sorrow” invites irony into how to read the poem's interrogation of ideological values. That the speaker decides not to “gather at the river” suggests a refutation of an ideological ground which relegates gays to a social level equal to fish. And rightly so: zoomorphism has long been a strategy for reducing some humans to subhuman status, from the metaphors of dogs fighting over a corpse in The Iliad, to any genocidal abuse which relegates some humans to subhuman status.

I bring in these last, broader comparisons to show the relevance of an ecopoetic analysis, as opposed to a taxonomic exercise between ecopoetry and nature poetry. I don't mean to argue the status of Ashbery's poem as an ecopoem, but to argue the merits of reading the poem ecopoetically.

Herein lies my problem with Shoptaw's position: there are numerous mechanisms by which ecopoetic trends, themes and concepts might be read into any poem, be it a poem in an anthology of urban-themed poetry, such as City State: New London Poetry (which I've used for teaching ecopoetics), or Emily Bronte's love poems. Raymond Williams used Hesiod's 'Worksand Days' for one of his chapters in The Country and the City and does a fine job of reading out ideas of pastorality and nostalgia.

And yes, I don't entirely approve of the 'urban poetry' label either, given how built environments are as much habitats as a farm field; the dusty corner of a library, or the human body; an overgrown brownfield waste land or an AONB.

Ecopoetics adds a set of shiny new tools for reading any text, not just poetry. I've used ecopoetic tools and methods to read insect handbooks and UN climate reports, poems from The Arcadia Project (which Shoptaw draws upon in his essay), William Wordsworth's poetry and even marketing language attached to supermarket vegetable selections.

*

Tune in tomorrow for part 3!

---

[1] Interestingly enough, at the Berkeley Conference on Ecopoetics in 2013, Joshua Corey records Shoptaw's objection to the poem's inclusion in The Ecopoetry Anthology. Note the confusion even here over the differences between ecopoetic and ecopoetry. I'm firmly on the side of ecopoetics being a way of reading poetry; and the definition of poems as ecopoetic, or a category of ecopoetry, is an unnecessary distraction – I'm as opposed to the Fisher-Wirth and Street's anthology title as to Shoptaw's attempt to define a new taxonomy.

Labels:

because no,

ecopoetics,

Essays,

John Shoptaw,

nature writing

Monday, 20 June 2016

George Ttoouli says, “Because: No.” (Or, Why Ecopoetics?) (1/5)

GT's

Essay B: a response to John Shoptaw's essay on ecopoetry

Published

in the January 2016 issue of Poetry (Chicago), John Shoptaw's

essay, 'Why Ecopoetry?' covers some helpful ground in accounting for

this relatively new poetry genre. Mulching over several key plots in

the current veg patch of US poetry, he points out the raised beds of

promise, the fecund spring bursts of colour and scent, the weedy,

gone-to-seed and bolted poems of yesteryear, the fallow ground where

environmental activism has taken hold in language.

By

now you're quite rightly thinking to yourself, 'You've exhausted the

soil of this metaphor, George. Get to the point!' For readers like

me, sceptical of the notion of poetry genres, there's a problem in

how a critical value system emerges through taxonomy. The

unacknowledged legislation in Shoptaw's essay is mainly signalled to

me by the failure to address why there's a need to genrify

ecopoetry.

A

key problem I have with 'ecopoetry' is that it struggles to separate

itself from 'nature poetry.' The same is true in Shoptaw's essay:

ecopoetry is both a subset of, but also distinct from, nature poetry.

Do we really need to say that the world has changed its way of

writing about nature because of climate catastrophe and

environmentalist awareness? Has every nature poem up to the invention

of the genre of ecopoetry been one bland long grass field mowed to a

fine metric, without variation? Every 'ecopoem' is also a 'nature

poem,' isn't it?

Shoptaw's

article starts from a negative response to that last question: an

ecopoem does, and must, challenge its readers to think morally and

politically about how we relate to nature, or relate culture and

nature. And not all nature poetry challenges.

But, but, I counter: every poem referencing 'nature', or,

preferably, human and nonhuman, matter living and nonliving, invites

engagement with the political and moral ramifications of the poet's,

the poem's and our own readerly values with respect to ecological

themes. This is Jameson 101, right? Even the avoidance of natural

imagery suggests a disengagement.

The

article sets out to establish a fourlegsgood/twolegsbad dichotomy to

evaluate poems. But this is critical elitism and does a mischief to

readers. Who's to say we can't think for ourselves, according to our

own terms? Argumentative readers, like me, might prefer to engage

afresh with eco-themes in poetry from any time or place, thinking

about today's particular eco-concerns by comparison. Instead, the

article hands over a badly made flail and tells us to start threshing

wheat from chaff.

A

covert problem behind genrifying ecopoetry is the lack of standards

in environmentalism. To say that you can define good and bad

environmentalism is like saying you could convince the CEO of Shell

to say, “You know, what the heck, I think we will keep it in

the ground!” Sure, there might be some extremes most of us would

agree on, but the question is decided by power structures, not some

distinct moral truth-object you can rub and make wishes come true

with. And I'd rather be allowed to formulate my own opinions on how

successfully any poem meets my highly subjective ecological

standards, than told what is wheat, what is chaff.

Every

nature poem can easily be argued to carry a response to the climatic

conditions, changes, developments, structural and content problems

inherent in the environment at the time of writing. Conscious or

unconscious, right or wrong. Even if the response now is to note

there's a bigger picture than the rough

winds shaking May's darling haws.

John

Clare's poem in the voice of Swordy Well lamenting the enclosure of a

piece of Northampton's commons doesn't need jazzing up by an ecopoet

for today. It's already a version of an environmental stance and

readers aren't so dumb as to be incapable of transposing a 200yr old

poem's message into relevant contexts today, be they digital (as,

e.g. Lewis Hyde noted of the new enclosures), or corporate land grabs

in developing countries.

*

Next part tomorrow!

Labels:

because no,

ecopoetics,

Essays,

John Shoptaw,

nature writing

Saturday, 18 June 2016

Simon Turner - The Portable Perec

I dream I am in a second-hand

bookshop (I often dream I am in second-hand bookshops), in this instance a beautifully

overcrowded one full of library stacks and reading tables o’ertopped with

ranter’s pamphlets and hardbound Victorian train timetables and antique maps of

the Hebrides. It’s a treasure trove, a

booknerd’s Nirvana, but my eye doesn’t linger long on the majority of the merchandise,

as something truly astonishing catches my eye: a black Penguin Classics edition

the size of a Gutenberg Bible called, with crashingly obvious irony, The Portable Perec. ‘Why have I never heard of this?’ I wonder,

and make my way to the book, which is so enormous, it has a long oak reading

table all to itself. I open the book at

random – though the word ‘book’ feels unequal to the task of describing this

wood-pulp leviathan: ‘tome’ seems so much more felicitous – a task that would

be a deal easier with two sets of arms instead of one, such is the sheer heft

of the volume. The contents are as marvellous as I could possibly

have expected: copious footnotes (in columns, no less!), a thirty page index,

illustrations from 16th century textbooks on natural history (they’re

the best), and more newly discovered Pereciana than you could possibly

imagine. (Though I clearly imagined it.) This is paradise; waking up will be harder

than ever.

Thursday, 16 June 2016

Wednesday, 15 June 2016

Minutes of the New Editorial Board Meeting

date: 24/5/16

present: RS, FS, GT, ST, Comrade Jesús.

Collectively to be known as 'The Editors ("Bastards")' in future.*

By founding editors GT & ST in this Revolutionary Year Zero, to new comrades, FS and RS and Comrade Jesús. Comrade RS offered compliments on the of commandeering of a ballroom for this occasion. Comrade Jesús praised the wine. FS paints the walls with slogans.

item two, initial intentions.

FS: Writing Inside vs. Outside of Academia

RS: In Praise of Precision

GT: A Response to John Shoptaw (-------**)

ST: Francis Towne conversational review with RS (-------**)

NB: Bracketed items may take longer than stated deadline (see item three).**

General discussion of possible article categories:

- Sacred Cow Patties

- Conversational Reviews

- (Aggressive) Interviews

- Lists of links / news

- "This week I have mostly been reading..."

- The Internet Forgets Nothing (a.k.a. 'From the Archives')

- Existentio-millennial Meltdown Corner (E=2MC?)

item three, deadlines.

1 June 2016.***

item four, AOB (what does this acronym mean? why is it even allowed?)

All Our Base

Anti-Oedipus Bust-up

Apple Or Barbiturate?

Acheron opens Bakery

Also Organic Babies

...

...

Further additions, emendments, variants, system dumps and data variances welcomed, likely ignored.

===

* With optional exemptions of Comrade Jesús and Bastards, according to context.

** Excised from public records so as to throw the enemy off the scent.

*** All dates are nominal/fictional. "Time does not exist" --Buddha, laughing.

Monday, 13 June 2016

Luke Kennard's Hills of Hamm

As stated in a previous email, these two Hamms were purloined by the Editors at a Buzzwords poetry event some years ago.

Our psychological experts are studying the handwriting for clues as to his psychic profile. However, recent evidence suggests Kennard, (a.k.a. 'Father K') has undergone counter-psych-profiling training with the aid of his Community Psychiatric Nurse (identity unconfirmed, suspected living embodiment of Biblical figure Cain) and any such profiling analysis will be redundant. It's like he's using his imagination or something.

Sunday, 12 June 2016

An Ecstasy of Looking - Simon Turner and Rochelle Sibley on Francis Towne

|

| Towne - A Sepculchre by the road between Rome and the Ponte Nomentana, 1780 |

ST: So,

Francis Towne. It feels entirely typical of Gists and Piths' approach that one of the first pieces we've posted since its reinstatement

is a review of an exhibition (which has been running since January) of an

obscure-ish English watercolourist (long since dead), detailing the

architectural revenants of a civilisation (classical Rome) that had given over

to inertia and decline many centuries before Towne arrived with his

paintbrushes. Read into that what you will. Nonetheless, the

paintings in the exhibition in question were genuinely a revelation.

Jonathan Jones had raved about them in the Guardian, and given that I usually

think he's an insufferable blowhard, I was initially sceptical, but it turns

out in this one instance his opinion was actually worth airing. These

paintings are, in a way, hymns to light, to the way light moves across the

landscape, across architectural detail, creating an architecture of its own in

shadow. I was just taken aback by them in a way I really hadn't expected.

RS: They

whipped it, didn’t they? I arrived at the exhibition with absolutely no idea of

what to expect (which is often my modus operandi), but these paintings were a

complete revelation. It took a while to work out why, but I think it has something

to do with Towne’s interest in the architectural detail of those ruins. It

would be easy to create something self-consciously Romantic from what is now

quite a hackneyed subject (and indeed some of the later, reworked paintings

edge towards this) but the paintings I most enjoyed were those where the

texture and patterning of the stones themselves were the focus. Despite the

locations themselves being almost overwhelming in scale, Towne is just as aware

of their fine detail as he is of their overall impact, which suggests a level

of obsessive observation that I can only admire.

ST: Yes,

the detailing was eye-catching. I think

part of the reason they were so surprising as a series was that we’ve been led

to believe (wrongly) that watercolour is a medium that favours gauzy abstraction,

whereas if you’re after hard and glittering detail, oils are the paints for

you. It’s a very English tradition, in a

way, painting en plein air well before

it was popularised by the French, but painting in the open in England means

rain, means mist, means a landscape that’s almost perpetually veiled and

blurred. But there’s none of that in

Towne (partly due, I’m sure, to the fact that it rains less in Italy, but also

because that’s not the way Towne’s eye is inclined): these are deeply architectural pictures, not simply

because of the subject matter, but because of the sculptural uses to which

Towne puts the light. There’s so much

weight to these paintings, even as they’re so filled with light and space.

|

| Towne - Inside the Colosseum, 1780 |

RS: I

think you’re right, watercolour as a medium often gets a raw deal in the popular

imagination. It’s often associated with the kind of appallingly precious flower-strewn

landscapes that only surface as budget jigsaw puzzles, when actually

watercolour allows for a lucidity and precision that is very difficult to

achieve with oil painting. Watercolour Challenge

has a lot to answer for. Admittedly,

it’s far easier to paint en plein air with

watercolours since you don’t have to worry about passing insects getting stuck

to your canvas, but watercolours are too often viewed as sketches rather than as

finished works. It speaks volumes that Towne left this collection to the

British Museum because at that point the Royal Academy didn’t consider

watercolours to be “proper” art. But this exhibition included a couple of the

oil paintings that Towne based on the watercolours, and they just don’t have

the same impact. In oils, the ruins feel stolid rather than substantial, and

without the translucency of watercolour even the natural elements of the

landscapes feel flat rather than three dimensional.

ST: It’s the difference between the world seen with the naked eye,

and the world as envisaged by a particularly Romantically-minded

cinematographer, isn’t it? And it’s a

shame, in a way, that Towne felt the need to try his hand at oils, because

watercolours were clearly his medium; he very much made them his own. I kept thinking about the notion of the watercolour

as preliminary sketch during our time in the exhibition, and its relationship

to writing. Watercolours are, or can be

conceived as, the visual equivalent of a writer’s journals: they’re not the finished

work, but point to the possibilities of the finished work. But I increasingly find journals and diaries

exciting in and of themselves: I find, too, that they age better than the ‘finished’

work from the same era. Dorothy

Wordsworth’s journal entry on the stand of daffodils that inspired Wordsworth’s

‘I wandered lonely as a cloud’ reads, give or take a couple of era-specific particularities

of phrasing, as though it were written last week. Old Bill’s poem, excellent as it is, has its

period written through it like Blackpool through a stick of rock. The same pertains to watercolours and oils of

a given era. The ‘serious’ painting in

the 18th and early 19th centuries is, primarily,

narrative, or mythic: the landscape has to mean

something, and however well-executed the incidental details of the painting, it’s the meaning that dominates.

For Towne, it’s the act of looking that’s the subject, chiefly, or that’s

my reading, at least: these

paintings are ecstatic acts of looking,

and looking closely.

RS: And also of trusting your artistic judgement to a different

degree than you see with the oil paintings. There’s an immediacy to the

watercolours that comes in part from the nature of the medium. You haven’t got

time to mess about, particularly in a Mediterranean climate. The exhibition

made me think of Georges Perec’s Bartlebooth, knocking out a watercolour

seascape in an afternoon. The best watercolours have that level of confidence,

and Towne’s work better than his oils because he hasn’t second guessed himself

too much about the composition or the palette. Plus that impressionistic quality

is more realistic to our eyes; it allows the artist to make a choice between

polished detail and blurred background, while the painterly tradition of Towne’s

era demands a more consistent level of focus throughout the plane of vision. With

these watercolours you have more room, as a viewer, to fill in those subtle gaps

yourself rather than having every element of the painting wallop you over the

head with its intended meaning.

|

| Towne - Inside the Colosseum, 1780 |

ST: That’s why they feel so modern, or not so era-bound at any

rate. I think, post-impressionism, we

have a different conception of what a landscape painting should do.

That narrative tradition has died out, by and large – though painters

like George Shaw are renewing the hyperrealism of the older tradition in

mutated form – and there’s no way back as a viewer to really see what

contemporary audiences would have seen: we can only talk about technical

details, the quality of the light, the composition, and so forth. (Also worth noting is the fact that this

allows previously comparatively neglected figures, like Samuel Palmer and Towne

himself, to be rediscovered and reappraised.) Maybe the contemporaneity of Towne’s Rome

paintings is aided by the absence of historical detail from his own period:

these Roman revenants have been around forever, or may as well have been – they’re

almost natural rather than historical phenomena, like the trees and the cliffs

they’re set among – and the few scattered figures that do appear scurrying

through the huge stone corridors are sketched in a rather cursory manner (quite

at odds with the palpable architectural presence of the ruins themselves), in

such a way that they could be Italian citizens who’d wandered into the frame

during Towne’s sketching of the scene, or they might just as readily be ghosts,

or flash-forwards to our own era. You

get the sense that these paintings will feel just as fresh in 100 years’ time

as they do now.

RS: I need some lunch. (Gannettry

ensues.) Right. Those little figures, who are often absolutely dwarfed by the

rest of the composition, are a wonderful example of all the things we’ve been

talking about. The oil paintings of these scenes do sometimes have people in

them, but they tend to be quite awkward, fixed little manikins who are eternally

of their own time. In contrast, the vagueness of the watercolour figures allows

them to exist outside time, particularly since their clothing is so lightly

drawn as to be as suggestive of togas as it is of more contemporary dress. They

don’t anchor the painting to any specific time, but they also remind us that

these are landscapes that you can move through. In fact, Towne’s tiny people

remind me of the blurred figures captured in early street photography, where

you only get a sense of an individual’s movement through space rather than of

their face. It adds something almost improvisatory to the paintings, so that

you have an appreciation of the scale of the ruins without some ponderous

numpty throwing allegorical shapes and generally undermining the sense that

Towne has captured a single flicker of time out of all the ages that these

buildings have been standing. That might be why I like these watercolours so

much, you have the sneaking feeling that if you turn away from one and then

look back, those little figures might have moved. Not in an M.R. James, scare you straight kind of way, but rather that they are just getting on with the rest of their day.

ST: Clearly lunch was an excellent idea: I really like your point about

early photography, and it’s never a bad thing to shoehorn an M. R. James

reference into an exhibition review. I’m

sure there’s more we could say, but nothing we could add would be a match for

the paintings themselves. The Townes are

on display until mid-August, so I would urge anyone interested to make their

way to the British Museum as soon as humanly possible. Right: shall we post this and go and do

something productive with the day instead?

RS: Lunch is always a good idea and yes, let’s trundle off,

possibly to find cake.

ST: Capital! Avanti!

Friday, 10 June 2016

James Schuyler's Live Debut, 1988

This is, I guess, the poetry equivalent of finding the cut scenes from The Magnificent Ambersons in a warehouse in Milton Keynes: incredibly rare footage that resurfaced last year of James Schuyler's first ever poetry reading in 1988, at the DIA Art Foundation. Schuyler, a poet I've loved for a very long time, was famously reclusive (which is particularly notable given the egregious gregariousness of many other members of the New York crowd), so this reading marks something of an historic event. The reading's excellent, and there's a lovely introduction by John Ashbery, too.

Thursday, 9 June 2016

Flo Sunnen - Outgrowing, Still Writing, Just Because

FS on leaving Academia

Regardless,

I am going to hold up my ‘writer’ card and write, just because.

The reason this will be a personal rather than academic or generally

‘serious’ essay is that I’m still figuring stuff out. I’m a

new member to the outside world, and by outside world I mean the vast

expanse of space and noise outside of Academia. I’ve been a part of

Academia for the past 10 years of my life, as a student, and I didn’t

exactly plan towards an academic career or any kind of viable future

inside the institution.

*

Now

that the context is different, and the structure is gone. I write and

feel guilty for writing, for wanting to write. It doesn’t feel

serious any more, doesn’t feel like it’s going anywhere. The

mindset has switched from ‘I am allowed – required – to do

this’ to ‘Do I still belong here?’ Writing needs work even when

no writing is being done, and a lot of this work is creating

motivation, making the creative process feel like a valid way to

spend a day, a life. So what I’m trying to figure out now is how to

ward off the voice inside that says, ‘Do something better with your

time’ or ‘There is no point to this’.

*

My

official leave from Academia happened very recently, with very little

fanfare: my

student card simply stopped working and I was asked by email to fork

over some money for the privilege to attend my own graduation. Like

that's ever going to happen. The weird thing about it is that I

thought it would be very different, and by that I mean I thought it

would feel

very

different.

*

It

shouldn’t be that difficult to keep the routine going, the one I

established while finishing my MFA project. Yet for some reason,

writing inside an academic framework and writing in the ‘real

world’ are two different beasts. The academic structure gives you

goals, focal points, a whole system by which to evaluate your work;

it gives you (more or less involved) supervisors, a peer group,

sometimes even a place to work. You work has a context, a set of

rules to follow, and a guaranteed audience.

*

I

know that self-motivation and self-imposed deadlines are a thing, a

thing many functioning adults do on a daily basis – I know about

project management, whatever. The problem is that they’ve never

been a reality, until now. Being outside of Academia is a vast field

of decisions waiting to be made, decisions which need to be made by

me rather than by anyone else; and the criteria are unclear. Inside

Academia, you are a student, and then you work towards becoming an

academic, I suppose. There are a limited number of roles, especially

if what you want to do and be paid to do is write.

*

This

is becoming about appearance, about seeming

serious and grown-up. And about how quickly time passes when you are

someone like me who takes a while to make decisions for herself.

*

Outside

of Academia, things are a little different. First of all, the

existential dread of ‘what am I even writing for’

is harder to ignore. You’re not writing for your supervisor, for a

mark, because it’s part of your degree.

*

I

started my Masters in Creative Writing in 2013, then moved on to an

MFA in 2014, and it took me about two and a half years to start

taking writing seriously, giving priority to my own writing process.

Because this ‘maturing’, shall we say, took place within

Academia, I now find myself lost outside of it.

*

Outside

of Academia, you can potentially be anything, and that’s a lot to

consider. Writing becomes vague, more self-conscious of its

vagueness. You become more aware of not having anything to say,

which wasn’t so much of an issue when you were still a student.

*

Sure,

I've honed some of my skills by staying in Academia for so long, I've

given myself time to figure out what I wanted to do, and, yes, I've

in some sense accepted my own slow growth. But I've also protected

myself from the chaotic vastness and confusion of the so-called "Real

World", another institution, really, or cluster of institutions

that lie outside of the academic fortress.

*

Outside

of Academia is vaster and more confusing, but not all that different.

I can still be rejected or ignored or made to feel inadequate, it's

just that the criteria by which others can do so are less clearly

defined – if anything, compared to Academia, there are more of

those criteria for me to contend with.

*

During

my 10 years, I did the most frowned-upon thing: I lived my student

life as a full-time thing. By that, I don’t mean that my studies

were always full-time, but rather that I didn’t supplement by

getting a job or gaining experience (padding my portfolio, so to

speak) outside of my studies, or even tried to gain experience

working (teaching) at university. I was simply a student for 10

years, first in Philosophy, then in Creative Writing, and that’s

it.

*

What

I want to say to myself is this:

You've

left Academia. That’s okay. You’ve chosen not to be an academic.

That’s okay too. You want to write. This is not a crime.

*

I

suppose the main problem is that, out here, writing feels more

frivolous than it did during my degree. Coming from Philosophy, it

took me a while to accept that writing could be a legitimate field of

study, something to be learned and practised in a structured course.

When I started accepting it, the writing itself became easier: I

learned to immerse myself in writing as my ‘work’, something I

was allowed to spend my time doing because I was doing it in the

context of a degree – it was legitimate for me to sit around and

think about writing because this was what I was supposed to be doing,

this was what I was supposed to be learning, and, ultimately, what I

would be marked on when I handed in my portfolio.

*

Oh

look, it’s everyone’s favourite:

a personal essay.

*

In

choosing writing over the continuation of my student life I feel like

I've escaped something that wouldn't have made me happy; at the same

time I also worry that I've chosen the less admirable route, the one

less likely to lead to success. Leaving feels like a failure (it's

not that I'd been working particularly hard towards an academic

career, I just always sort of assumed I'd end up in one), and I worry

about what not wanting

Academia

more, not working harder at it, says about me. What it means is, I

chose writing instead, which seems so frivolous a choice, especially

given I don’t work at being a successful part of the industry.

*

The

problem is that I can't yet tell what will come of my decision.

During the last months of my MFA, I did all I could to avoid the fear

of what would come next. I told myself repeatedly I was doing the

right thing, that I was giving myself and my writing a chance. I

tried to convince myself that my writing would flourish outside of

Academia, and so would I. I would be freed of a system of evaluation;

my self-worth would no longer be rooted in praise and acceptance; my

reading lists would be my own.

*

Without

the assignments and deadlines, I'm not longer sure what it is I'm

writing for,

so I suppose it may as well be for myself. This won't keep me safe

from rejection, of course, nor from criticism. The people who will do

so will probably often be a lot less well-meaning, equipped with a

lot less pedagogical training, and generally more confusing in their

tastes than my professors used to be. Their feedback might be cryptic

or it might relate to themselves much more than to my output. I might

just be dismissed offhand.

*

It's

something to grow into, I guess.

Labels:

academia,

Essays,

personal essays,

the writing life

Tuesday, 7 June 2016

Melon 'n' Dome

Lone 'n' Modem

End mole mon

Nom le Monde

London Em-O-Em

Mend no Elmo

Ne do le mm! No!

Labels:

anagrams,

music,

unsettling juxtaposition,

Video

Sunday, 5 June 2016

Simon Turner - "Happy for now to let the mystery stand"

1.

Half-writing and half-reading in

the garden, though concentrating fully on neither if I’m honest with myself:

just sitting, in truth, not thinking, watching the passage of the light, the

wind passing through the leaves of the copper beech. In the distance, an old oak on what passes

for a hill in the flat landscape, where crows and jackdaws come and go,

disappearing instantly in its dense black canopy. Leaf-flicker on brick path, the flower beds

blowsy and ragged this late in the summer.

A few light clouds amble across the comic-book blue of the sky, and

then, amazingly, a bird of prey, without doubt, swoops lazily overhead,

briefly, all too briefly, seen between the treetops and the house-tops. Its underside a uniform buttery cream – like beech

wood freshly gleaming through a wound in the bark – apart from two black,

comma-shaped patches on each wing-hinge, a notable marking made all the more

vivid by the cleanness of the surrounding colouration. A search through books and internet sites

brings nothing: it’s the wrong size – or I guess it is from the short time I

saw it – for a honey-buzzard, though that’s the only possible suspect for a

bird with those markings (honey-buzzards, though not a fixture, are an

occasional visitor to this stretch of coast), and everything else is too fanciful

to even begin to countenance. Happy for

now to let the mystery stand.

use of space. Then the suspicion of an

awkwardness. I had thought there were two pairs

of harriers. One of the four is not.

The graphics roll into a scuffle, bind

a confusion, wrestle themselves for a

discovery. The sky is opening

to the touch of an anomaly: the

other bird, full splay, stamped with black on both

its wrists.”

R. F. Langley, from ‘Vidilicit’, in Complete Poems, ed. Jeremy Noel-Tod (Manchester: Carcanet, 2015)

Saturday, 4 June 2016

Some sporadic news items

Luke Kennard has a new book out: Cain

It looks like this on my desk:

You'll notice, next to it, a postcard, one of fifty limited edition 'bonus poems' sent out with the first 50 pre-orders. You don't get to read it unless you pre-ordered. Or if you come round my house and strong-arm me into showing you my copy. But you will first have to be restrained, Hannibal Lecter style, and wheeled into the special viewing vault I have constructed, and you will be behind Perspex in case you splutter your dirty juices all over my precious postcard poem.

The Editors do have an exclusive LK unpublished poem draft,snatched from his bag acquired through legal channels at a Buzzwords event some years ago, apparently during a Matt Merritt workshop. It will go live soooon.

+

Luke's launch took place at the Waterstones in Birmingham's New Street, just by the rail station. This is apparently to be a regular open mic type thing. This month (June 6th), however, Nine Arches Press are launching volume one of Primers. Kind of their answer to the Faber New Poets, and put together with The Poetry School, the project seeks out new poets and launches them into the stratosphere, or, well, as high as a punk-poetry Midlands-built rocket can send them.

I can only find an online flyer image on twitter, so that's what you get now:

I also know nothing more about the open mic at the Waterstones during Luke's launch because it was on a chalk board at the event and I wiped my brain cells of the entire evening when I got home so I could enjoy the printed poems afresh when the book arrived. Anyone has any info, wants to go, ping us. Then again, I may find out on Monday at Primers.

+

Peter Blegvad has a new radio play, 'The Impossible Book', airing on BBC R3's Between the Ears, Saturday 11th June, 21:15-21:45.

I have heard a sneak preview. It features Peter Blegvad as an unnamed writer, and Harriet Walter as Agatha Christie. It is phenomenally weird and beautiful. Produced with Iain Chambers, sound designer extraordinaire.

The short description is: "A writer is beset by hallucinations on a train travelling through time and space."

The long description, available here, hints at the depth of strange beauty at work in Blegvad's mind, and in the resulting play, spawned, so I hear, from a project originally begun around 20 years ago.

The BBC's mid-length description is entertaining because it doesn't quite make sense. Which is a really, really good sign.

+

Midlands Creative Projects have teamed up with Bloodaxe Books once again to create a live poetry extravaganza. It is on at the Belgrade Theatre for two nights only, 1st and 2nd July:

Beyond the Water's Edge

The Editors are sad they can't go. Anyone who goes and would like to write up their response to it, would be most welcome to air their views here. Post a comment or something, saying you're going and will send us words. In fact, we'll gladly publish multiple responses, by anyone willing to send us three words, three hundred, or even three thousand on the subject. (Once we've run it past our legal team and you've signed a disclaimer taking full responsibility, etc. etc.)

+

There is a new journal emerging, called Epizootics, which self-describes as an "Online Literature Journal for the Contemporary Animal":

+

The Enemies Project, long may it continue, recently partnered with Singing Apple Press (Camilla Nelson) for a tour of the South West later this year.

While the deadline has passed for participation, it does make the Editors wonder why so few poetry-related tours from outside the WMids manage to penetrate the huge 300 foot wall of the imagination surrounding us. Well, fail to leave the motorway exits. Maybe they're all like Philip Larkin, watching from a train...

+

Hannah Silva's Schlock! is going to be in The Rosemary Branch theatre in London for most of November. Start planning it now.

I watched a preview several months back and it was upsettingly good. I mean upsetting and good. Or, well, something. Here is a promo video:

It looks like this on my desk:

You'll notice, next to it, a postcard, one of fifty limited edition 'bonus poems' sent out with the first 50 pre-orders. You don't get to read it unless you pre-ordered. Or if you come round my house and strong-arm me into showing you my copy. But you will first have to be restrained, Hannibal Lecter style, and wheeled into the special viewing vault I have constructed, and you will be behind Perspex in case you splutter your dirty juices all over my precious postcard poem.

The Editors do have an exclusive LK unpublished poem draft,

+

Luke's launch took place at the Waterstones in Birmingham's New Street, just by the rail station. This is apparently to be a regular open mic type thing. This month (June 6th), however, Nine Arches Press are launching volume one of Primers. Kind of their answer to the Faber New Poets, and put together with The Poetry School, the project seeks out new poets and launches them into the stratosphere, or, well, as high as a punk-poetry Midlands-built rocket can send them.

I can only find an online flyer image on twitter, so that's what you get now:

I also know nothing more about the open mic at the Waterstones during Luke's launch because it was on a chalk board at the event and I wiped my brain cells of the entire evening when I got home so I could enjoy the printed poems afresh when the book arrived. Anyone has any info, wants to go, ping us. Then again, I may find out on Monday at Primers.

+

Peter Blegvad has a new radio play, 'The Impossible Book', airing on BBC R3's Between the Ears, Saturday 11th June, 21:15-21:45.

I have heard a sneak preview. It features Peter Blegvad as an unnamed writer, and Harriet Walter as Agatha Christie. It is phenomenally weird and beautiful. Produced with Iain Chambers, sound designer extraordinaire.

The short description is: "A writer is beset by hallucinations on a train travelling through time and space."

The long description, available here, hints at the depth of strange beauty at work in Blegvad's mind, and in the resulting play, spawned, so I hear, from a project originally begun around 20 years ago.

The BBC's mid-length description is entertaining because it doesn't quite make sense. Which is a really, really good sign.

+

Midlands Creative Projects have teamed up with Bloodaxe Books once again to create a live poetry extravaganza. It is on at the Belgrade Theatre for two nights only, 1st and 2nd July:

Beyond the Water's Edge

The Editors are sad they can't go. Anyone who goes and would like to write up their response to it, would be most welcome to air their views here. Post a comment or something, saying you're going and will send us words. In fact, we'll gladly publish multiple responses, by anyone willing to send us three words, three hundred, or even three thousand on the subject. (Once we've run it past our legal team and you've signed a disclaimer taking full responsibility, etc. etc.)

+

There is a new journal emerging, called Epizootics, which self-describes as an "Online Literature Journal for the Contemporary Animal":

"We are currently accepting submissions for our first issue, to be published online in August. We accept experimental poetries and prose, as well as criticism, philosophy, theory and reviews. Exact specifications can be found on our website. Send 3-5 poems or up to 5000 words of prose to their email address. We also particularly encourage long poems, serial poems and mixed genre works."

+

The Enemies Project, long may it continue, recently partnered with Singing Apple Press (Camilla Nelson) for a tour of the South West later this year.

While the deadline has passed for participation, it does make the Editors wonder why so few poetry-related tours from outside the WMids manage to penetrate the huge 300 foot wall of the imagination surrounding us. Well, fail to leave the motorway exits. Maybe they're all like Philip Larkin, watching from a train...

+

Hannah Silva's Schlock! is going to be in The Rosemary Branch theatre in London for most of November. Start planning it now.

I watched a preview several months back and it was upsettingly good. I mean upsetting and good. Or, well, something. Here is a promo video:

Labels:

Bloodaxe Books,

Hannah Silva,

Luke Kennard,

Midlands Creative,

News,

Nine Arches Press,

penned in the margins,

Peter Blegvad,

theatre

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)