Monday, 10 October 2016

Saturday, 8 October 2016

Rochelle Sibley – Adventures in Yiddish (7): Nahum Stutchkoff, hero of Yiddish

One

of the many joys of learning a new language is encountering new writers you’ve

never even heard of before. Until two

years ago I knew spectacularly little about Yiddish literature, so most of

these discoveries are just long overdue, but occasionally a writer turns up who

is of such significance that I can’t believe I missed them for this long. Nahum Stutchkoff (1893-1965) fits that

category. I’m calling him a writer, but

that’s not really an accurate description of his achievements. He did write radio plays and advertisements, but

he was also an actor; he was a radio presenter but he was also, and most

importantly for me, an exceptional linguist and lexicographer. Without him, our understanding of Yiddish

today would be considerably impoverished.

Stutchkoff’s

two great Yiddish publications are his 1931 Gramen-lexicon

(Yiddish rhyming dictionary) and his incredible 1950 Oytser fun der yidisher shprakh (Yiddish thesaurus). These two

deserve blog posts of their own (and will be getting them), because each

illuminates a different aspect of why Yiddish kicks ass. The Oytser is the

most beautiful of all my dictionaries (that’ll be dictionary number seven), and

the one that best encapsulates the flexibility and variety of the Yiddish

language. The Gramen-lexicon

(dictionary number eight – yes, I have a problem) is a wonderful creation, made

even more appealing by the fact that Stutchkoff used it to help him write

advertising jingles for his radio shows.

From

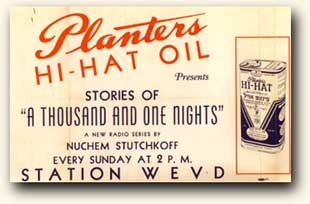

1932, Stutchkoff worked as a presenter at the Forverts radio station WEVD in

New York, but of all his broadcasts it’s Mame-loshn that really stands

out to a Yiddish learner. This show ran for

over 600 episodes from 1948, and was all about sharing the richness and

adaptability of the Yiddish language. Although

I’ve not been able to uncover any recordings of it, in 2014 Forverts published

a collection of segments from Mame-loshn, all of which are based on

Stutchkoff suggesting English words for Yiddish terms, and visa versa. He might have been a scholar of language but

this dude was interested in how Yiddish was used in the everyday and, as such, his

writing is way past some of the restrictions imposed by the standardized YIVO

version of Yiddish that I’m learning. I’ve

no wish to undermine YIVO Yiddish – without YIVO it’s doubtful I’d be in any

position to learn the language at all – but standardization always comes at the

cost of regional variety and other linguistic idiosyncrasies.

This

is where Mame-loshn really delivers. Stutchkoff’s responses to his audience reflect

the diversity of Yiddish terms, acknowledging the different linguistic branches

to a level of detail that even my eight dictionaries are hard-pressed to match.

A personal favourite is his reply to a

woman who asked about the Yiddish word for “gravy” or גרײװי. Stutchkoff advises those his listeners from Warsaw that they would

have said “brotyoykh” and “gebrotene”, while “zuze” and “zshuzshe” were also

popular in other Polish areas. However, Stutchkoff

continues, in Lithuania the term was “tunk” (a word I’ve never seen in any of

my main dictionaries), and he thought that this was the most pleasing option

because it suggests “a sauce that isn’t for eating and isn’t for drinking, but

rather is for dunking”. [1]

It’s

this love of language for its own sake that makes Stutchkoff such a hero of

Yiddish. Mame-loshn shows Yiddish in the process of adapting to life in the

US, creating neologisms and adopting Americanisms as it went. Not that Stutchkoff was unaware of the threat

to Yiddish: he wrote the Oytser fun der yidisher shprakh in the hope of preserving Yiddish after the Holocaust. However, what is clear from Mame-loshn is that Stutchkoff was very

much against preserving Yiddish in stasis. His love of the language was always dependent

upon it being alive and therefore capable of evolution, and despite his desire

to see Yiddish survive, he was remarkably pragmatic about the challenges it

would face. The best way of seeing this

is for me to translate the segment on “Gosh” in full, in the hope that some of

Stutchkoff’s inherent cheekiness and conversational wit come through: [2]

A Jewish Woman from the Bronx pours her bitter heart

out to me: ‘I have,’ she writes, ‘a little boy who goes to a Jewish school and

studies very hard, but it is becoming very difficult to persuade him that he

should speak Yiddish at home. What does

he claim? That it’s too difficult for

him. Recently I shouted at him: “You

should listen to me, every minute with your “Gee” and with your “Gosh”!” He raised up to me a pair of innocent eyes and

said, “How do you say “Gee” and “Gosh” in Yiddish?” I didn’t know how to answer him. Truly, can you help me, Mr. Stutchkoff? I have told him that I will ask you.’

I can help you. I can tell you how Jewish children in the old

country used to express their surprise when they didn’t know “Gee” or “Gosh”,

but they spoke Yiddish and so their sayings sounded right. Perhaps they wanted to fit in with the other

little Jewish boys, I don’t know. When a

little Jewish boy felt really surprised, he used to shout: “OY! Mamelekh!

Tatelekh!” or (in Lithuania): “Maminke! Tatinke!”.

Or he used to say: “Really?! What are

you talking about? Ze! Ova! Oy-oy-oy!” And

so, he would fit in with all the other little boys.

In

that one response, Stutchkoff highlights not just the fact that there is rarely

only one way to translate any word into Yiddish, but also acknowledges that for

the next generation of American Jews, Yiddish was always going to play second

fiddle to English. However, thanks to

his epic efforts to capture the Yiddish he knew as a living, breathing

language, those of us in the generations that followed can still experience

Yiddish in all its messy, non-standardized glory. Despite his understandable fears for Yiddish’s

future, Stutchkoff created some of the best resources for ensuring its

continuing survival not only as a point of historical or literary interest, but

also as a language of gossipy backchat. In

Stutchkoff’s view of Yiddish, bedspreads and window blinds are just as relevant

as matzo and gefilte fish to American Jewish life. Thanks to him, I can write Yiddish limericks

and understand phrases that no longer appear in any modern Yiddish dictionary. If he were still alive I’d buy him a pint, but

in lieu of that I’ll just have to say, װאָס אַ מענטש.

[1] No surprise that the Yiddish word for “dunking” is “tunken”.

[2] The initial paragraph is the listener’s letter, while the section in bold is

Stutchkoff’s response, or as close as I can render it. Even with eight dictionaries, there are words

here that I can’t find.

Friday, 7 October 2016

Flo's Friday Doodles #1: Silverscape (water)

Wednesday, 5 October 2016

Simon Turner - About the Author (1)

Calliope

Wagstaff walked barefoot from Jamaica, and a number of her outpourings have

lassoed themselves around her crenulations there. Veritably she is a centaur who tries to

recognize something mythological whiffling through the fog of an uncorked July,

and quite often retreats into the grykes and cleats of her tenuous marriage. The two ‘Belgian roses’ appended here are

both concerned with unexpected adultery and the coast of Greenland: her twinned

secret asylums. ‘The Beating of the

Demons’ displays a grimace of brazenly elaborate colour and depth which appears

nowhere else in her egg-box. Her

publications include: The Shadows of the

Mandarin (Jubjub Books, 1979), The

Glaciers (Beltane Umbrella, 1983) and Just

Like the Horizon (Thamescape Press, 1991).

Monday, 3 October 2016

Signs and their Portents #4: "Frightened Gloss"

"The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown."

HP Lovecraft, Supernatural Horror in Literature

*

JG Ballard, advertisement, Ambit #33, Autumn 1967

*

"Johansen swears he was swallowed up by an angle of masonry which shouldn’t have been there; an angle which was acute, but behaved as if it were obtuse."

HP Lovecraft, The Call of Cthulhu

*

*

"Everything he saw was unspeakably menacing and horrible"

HP Lovecraft, The Dreams in the Witch House

*

Saturday, 1 October 2016

Masterpieces of Cinema (2): Rochelle and Simon tackle Hitchcock's Shadow of a Doubt (1943)

RS:

Right, full

disclosure time: I have a slightly disturbing and vaguely inexplicable love for

Joseph Cotten. Actually it’s not inexplicable, the man

was a fox. However, this is not the

reason why I think that Shadow of a Doubt

is Hitchcock’s best film (Hitchcock himself thought the same, by the way, but

I’m not expecting anyone to take that wily bastard’s word on anything). When I was re-watching it for the umpteenth

time last week, I realised that its genius hinges on the subversive and often

downright inappropriate relationship between Uncle Charlie (Joseph Cotten) and

Little Charlie, his niece (Teresa Wright). On previous viewings I’d picked up on the

dodgy incest subtext, which is difficult to miss since so many of their scenes

are staged to echo the standard romantic clichés of the time. There’s the usual joyful reunion at the

station, complete with them running into each other’s arms, as well as all

those adoring glances and passionate declamations of mutual admiration, to say

nothing of Uncle Charlie’s present to Charlie, that emerald (engagement) ring,

engraved with someone else’s declaration of undying love.

What I noticed this time, though,

was just how much mirroring Hitchcock creates between these two namesakes. In fact, each of the Charlies is introduced in

exactly the same way (lying on their bed staring vacantly into the middle

distance) in similarly composed shots, just with the staging reversed. The film appears to be asking, if they’re so

similar, why is Uncle Charlie such a murderous psychopath, when Little Charlie

is an apparently blameless and intelligent young woman? Was it nature or

nurture that made him this way? Or is it that Little Charlie has the same

potential for violence, if circumstances require it?

ST: I would suggest the latter, to be

honest: Uncle Charlie’s violent tendencies are given some kind of contextual

gloss – there’s a suggestion that a childhood accident might have unlocked some

previously dormant side of his personality – but it’s perfectly clear to me

that we’re meant to read his sociopathy as essentially innate, given free play

by a combination of upbringing (over-indulgent parenting is definitely in this

movie’s sights as a subject ripe for critique) and opportunity. Young Charlie, meanwhile, is perhaps not

indulged to the same extent as her uncle, but she has a restless, refusenik

quality in common with him, which simply finds different outlets.

When reading Hitchcock’s movies,

it’s often instructive to see where they fit in his chronology, and Shadow of a Doubt falls slap in the

middle of a really interesting run of films Hitchcock made in the 40s after

having emigrated to the States. With the

exception of Mr and Mrs Smith (1941),

which I don’t think Hitch was 100% satisfied with, his films from Rebecca (1940) through to and including

Notorious (1946) follow the same pattern: nominally apolitical psychological

thrillers about a family hiding a dark secret (usually a murderer),

interspersed with more overtly, though ambiguously propagandistic films about

the growing threat of European Fascism (this agitprop component of Hitchcock’s

output’s most overtly on display in Foreign

Correspondent [1940], although Saboteur

[1942], Lifeboat [1944], and Notorious [1946] all qualify as

‘anti-fascist’ to a greater or lesser extent).

Why ‘nominally’ apolitical? Why ‘ambiguously’ propagandistic? Let’s take Shadow of a Doubt as a case in point, as it’s the best of his 40s

films, and the most troubling from a number of standpoints. The apolitical reading would ground this

solely in the familial narrative: yes, it’s undergirded by some really

troubling Freudian connotations; and yes, it suggests the wholesome Rockwellian

all-American family might not represent the untroubled Eden of the

Eisenhower-era mythos; but even taking these facets of the narrative on board,

it would be possible to begin and end your reading of the film within the

limits of the family homestead, and not have to worry about what Hitchcock

might be saying about the historical moment.

But what if we did bring specific political events into play? What if we accept Uncle Charlie as an

explicit representation of Fascist threat – some of his speeches about the

‘bestiality’ of rich women suggest we’re definitely meant to read the film in

this way – and Young Charlie’s gradual realisation of her uncle’s misogynistic

perfidiousness as an analogue for the awakening of the American people to the

scale of the threat waiting for them on the other side of the Atlantic? Then we’re wading into much murkier and

interesting territory, right?

|

| Joseph Cotton (far right, next to the horse), in Horse Eats Hat (1936) |

RS:

I think so, because

there is the distinct suggestion that Little Charlie is prepared to overlook

her uncle’s murderous habits just as long as he leaves quietly and doesn’t

cause an embarrassing scene. The film

questions the limits of what a decent person is able to put up with when it’s

other people rather than themselves that are under threat. The merry widow that Uncle Charlie encounters

in the bank is a case in point: there doesn’t seem to be much overt sympathy

for her imminent peril; rather it’s the family’s reputation that Little Charlie

is worried about. What’s interesting

here, though, is that she tells Uncle Charlie that if he doesn’t leave she’ll

kill him herself, which corresponds with the idea that such behaviour is innate,

but also considerably raises the narrative stakes: the audience becomes aware

that this is likely to be a battle to the death, rather than a straightforward

pursuit of hunter and prey. Perhaps this

chimes with the idea of the historical moment too, in that Little Charlie’s

worldview has been completely and irrevocably altered at that point, as though

she’s realised that it’s up to the person in the street to oppose the kind of

fascistic threat that Uncle Charlie represents. There’s just such a contrast between Uncle

Charlie and Little Charlie’s father, the latter being endlessly fascinated with

plotting the perfect murder, while the former actually carries them out. It feels as though the film is capturing that

moment when comparatively innocent game-playing switches to something far

darker.

ST:

I would read it as

more directly political than that: that Little Charlie’s father is able to

treat murder as a game or a past-time because he’s a ‘civilian’ in this world,

whereas the two Charlies are in effect combatants, well-versed in what violence

actually entails – a knowledge that bonds them together, however monstrously –

and incapable of communicating that knowledge fully to their friends and

compatriots. I think the reason I read

Hitchcock’s wartime movies as radically ambiguous in their propagandistic

motives – both the overt and covert pieces detailed above – is precisely

because they keep foregrounding these moral questions in a manner that’s

inevitably (and unusually) unsettling for an audience more acclimatised to

morally black-and-white accounts of anti-Nazi derring-do. In short, Little Charlie – like the ragtag

gang of shipwreck survivors in Lifeboat,

for example – must become the monster in order to defeat the monster. There’s no real sense of catharsis in her

defeat of her murderous relative in the final moments of this film, at least in

part because Hitch is very careful to render Uncle Charlie’s death in decidedly

uncertain terms – leaving it up to the viewer to decide whether his niece

pushes him from the carriage door with malice aforethought, or whether he

tumbles to his doom due to the caprices of accidental fate – but primarily

because we’re asked to contemplate what

comes after. Here’s a young girl,

remember, whose journey into the vagaries of adulthood has taken the form of a

struggle to the death with her serial killing uncle, and her success in this

grubby endeavour is predicated on the fact that she’s taken a human life,

however necessary and ‘moral’ that act might have been in the grand scheme of

things. Raising the spectre of Lifeboat again, there’s a very similar

moral journey made by the characters in that film, too, for all of the major

differences in narrative structure and setting: both films belong much more

readily to the ethical universe of film noir than to the more crowd-pleasing

cinematic war efforts that Hitch’s British compatriots were producing at the

same time.

RS:

I see what you mean

about the two Charlies being ‘combatants’

rather than ‘civilians’. In that

final scene with Little Charlie telling Detective Graham about how they are the

only ones who know the truth about Uncle Charlie, there’s a camaraderie that is

quite unexpected. It reads more like two

war buddies rather than the (slightly peculiar) romantic relationship that has

been developing over the second half of the film, and it’s another moment where

Hitchcock successfully exploits and then undermines the audience’s expectations

regarding Little Charlie’s future. Rather

than discussing marriage (like they were earlier in the film), Little Charlie and

Graham are talking about concealing the identity of a serial killer, whose

plaudit-filled funeral is still in progress. I suppose long-term relationships have been

built on less.

In terms of the noir tradition,

Little Charlie is a strange character. She’s

no femme fatale, and she’s not really the wholesome girl-next-door – at least,

not by the final reel. I’ve always

assumed that she does push Uncle

Charlie from the train, simply because if his death is accidental it makes the

ending neat and tidy rather than subversive and disturbing, and Hitchcock is

more about the latter than the former. In

fact, that scene always reminds me of the end of Sabotage (1936), another film about an unseen, anonymous threat to

democratic society (with added puppies), when Mrs Verloc stabs up her

treacherous terrorist of a husband after realising he inadvertently killed her

little brother (and the aforementioned puppy). You’d have to be a cold-hearted bastard not to

be hoping she gets away with it, but the fact that she does is still something

of a surprise. Hitchcock seems to be

interested in capturing that moment of conflict where the audience both

identifies with and is horrified by the protagonist, and there’s something similar

happening in Shadow of a Doubt. Little Charlie becomes almost monstrous and

definitely alienated in order to preserve her community’s innocence, and while

we don’t necessarily want to see her fail, it’s a profoundly uncomfortable

feeling when she succeeds.

|

| Hitch enjoying a modestly sized pretzel at the Psycho premiere |

ST: It’s something Hitchcock keeps coming

back to, even later on, isn’t it? Witness,

say, the scenes in Psycho (1960),

where the audience is drawn into Norman Bates’ (Anthony Perkins) attempt to

cover up ‘Mother’s’ murder of Marion Crane (Janet Leigh): we watch him clean up

the bathroom, remove the infamous shower curtain, and dispose of the

incriminating triumvirate of Marion’s corpse, baggage and car in the nearby swamp,

at all points horribly aware of how we’re being manipulated into some kind of

warped empathy with this morally repugnant man.

In Rear Window (1954), too, Hitch

repeats to trope of ordinary citizens stepping over the line of acceptable

legality to bring a miscreant to justice: Jimmy Stewart turns voyeur [1], Grace

Kelly gets involved in a little light breaking and entering, and they both

collude in an act of fake blackmail, all in an effort to entrap Raymond Burr’s

hulking ‘voluntary widower’.

But even in these instances,

Hitchcock never full-bloodedly returns to the truly murky moral universe of his

British and early American films, to my mind anyway (although the troubling

collusion between protagonist and antagonist in Strangers on a Train [1951] is probably the closest fit in terms of

mood and moral implications). It’s precisely

this murkiness – which has a distinct Patrick Hamilton / C S Forester [2] flavour

to it – which provides these films with their strength, and guarantees them their

premier position within Hitchcock’s output, with Shadow of a Doubt the grubby jewel in a deliciously tarnished crown. I do feel generally that the 30s and 40s get

a little neglected in coverage of Hitchcock as a director, though, with his

later films (Vertigo [1958] in

particular) tending to garner the most critical and audience attention at the expense of the earlier movies. Do you feel that’s the case?

RS:

Most definitely. My favourite Hitchcock film used to be Rear Window, which I still love, but

although it is so smart and visually inventive, there’s nothing like the same

level of unsettling confusion that makes Shadow

of a Doubt and the other earlier films so memorable. Discussions of Hitchcock’s later films can sometimes

seem to reduce his work to a succession of grisly deaths and foxy blondes, as

though his points of obsession became more pronounced in the second half of his

career. Shadow of a Doubt was a revelation because it has to operate within

the most extreme strictures of the Hayes code, and yet still produces the most

cold-blooded psychopath of Hitchcock’s entire back catalogue. Perhaps it’s those restrictions that promote

his creative inventiveness, or perhaps it’s just Joseph Cotten kicking ass, but

Shadow of a Doubt feels like a leaner,

more upsetting film than any of those later examples, and as such deserves more

recognition than it gets.

ST:

Indeed, and I’d

argue that genius in any artistic field resides not in total freedom and

creative control on the part of the artist, but rather in the capacity of the

artist to work within the codes and

restrictions of his/her period and still

produce a series of masterpieces (Hitchcock and his peers are no different to

the painters and sculptors of the Italian Renaissance in this respect). In curtailed and more controversial terms:

creativity is constraint. (That might be material for an entirely

different series of posts, however.)

More broadly, this period of Hitchcock’s – running from, say, the first

version of The Man Who Knew Too Much in

1934 to Notorious in ’46 – feels like

an untapped resource, a hidden treasure-trove, which, precisely because it

doesn’t get the same kind of coverage as the acknowledged classics that came

later, is yet to fully yield up its secrets.

I’d urge anyone who’s even slightly interested in film to delve, and

there’s no better place to start than Shadow

of a Doubt.

===

[1] Although the film’s real

interest lies in the suggestion that the voyeuristic impulse resides in all of

us: Stewart’s character is simply using a natural yet morbid human leaning to some

kind of societal good, albeit a deeply morally troublesome ‘good’.

[2] I’m referring to Forester’s

excellent trio of seedy, proto-Graham Greene crime novels, by the way, not the

Hornblower series of books, which are decidedly unmurky in character.

Labels:

At the movies,

Hitchcock,

Masterpieces of Cinema

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)