One

of the many joys of learning a new language is encountering new writers you’ve

never even heard of before. Until two

years ago I knew spectacularly little about Yiddish literature, so most of

these discoveries are just long overdue, but occasionally a writer turns up who

is of such significance that I can’t believe I missed them for this long. Nahum Stutchkoff (1893-1965) fits that

category. I’m calling him a writer, but

that’s not really an accurate description of his achievements. He did write radio plays and advertisements, but

he was also an actor; he was a radio presenter but he was also, and most

importantly for me, an exceptional linguist and lexicographer. Without him, our understanding of Yiddish

today would be considerably impoverished.

Stutchkoff’s

two great Yiddish publications are his 1931 Gramen-lexicon

(Yiddish rhyming dictionary) and his incredible 1950 Oytser fun der yidisher shprakh (Yiddish thesaurus). These two

deserve blog posts of their own (and will be getting them), because each

illuminates a different aspect of why Yiddish kicks ass. The Oytser is the

most beautiful of all my dictionaries (that’ll be dictionary number seven), and

the one that best encapsulates the flexibility and variety of the Yiddish

language. The Gramen-lexicon

(dictionary number eight – yes, I have a problem) is a wonderful creation, made

even more appealing by the fact that Stutchkoff used it to help him write

advertising jingles for his radio shows.

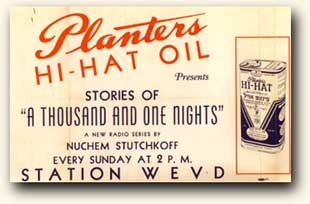

From

1932, Stutchkoff worked as a presenter at the Forverts radio station WEVD in

New York, but of all his broadcasts it’s Mame-loshn that really stands

out to a Yiddish learner. This show ran for

over 600 episodes from 1948, and was all about sharing the richness and

adaptability of the Yiddish language. Although

I’ve not been able to uncover any recordings of it, in 2014 Forverts published

a collection of segments from Mame-loshn, all of which are based on

Stutchkoff suggesting English words for Yiddish terms, and visa versa. He might have been a scholar of language but

this dude was interested in how Yiddish was used in the everyday and, as such, his

writing is way past some of the restrictions imposed by the standardized YIVO

version of Yiddish that I’m learning. I’ve

no wish to undermine YIVO Yiddish – without YIVO it’s doubtful I’d be in any

position to learn the language at all – but standardization always comes at the

cost of regional variety and other linguistic idiosyncrasies.

This

is where Mame-loshn really delivers. Stutchkoff’s responses to his audience reflect

the diversity of Yiddish terms, acknowledging the different linguistic branches

to a level of detail that even my eight dictionaries are hard-pressed to match.

A personal favourite is his reply to a

woman who asked about the Yiddish word for “gravy” or גרײװי. Stutchkoff advises those his listeners from Warsaw that they would

have said “brotyoykh” and “gebrotene”, while “zuze” and “zshuzshe” were also

popular in other Polish areas. However, Stutchkoff

continues, in Lithuania the term was “tunk” (a word I’ve never seen in any of

my main dictionaries), and he thought that this was the most pleasing option

because it suggests “a sauce that isn’t for eating and isn’t for drinking, but

rather is for dunking”. [1]

It’s

this love of language for its own sake that makes Stutchkoff such a hero of

Yiddish. Mame-loshn shows Yiddish in the process of adapting to life in the

US, creating neologisms and adopting Americanisms as it went. Not that Stutchkoff was unaware of the threat

to Yiddish: he wrote the Oytser fun der yidisher shprakh in the hope of preserving Yiddish after the Holocaust. However, what is clear from Mame-loshn is that Stutchkoff was very

much against preserving Yiddish in stasis. His love of the language was always dependent

upon it being alive and therefore capable of evolution, and despite his desire

to see Yiddish survive, he was remarkably pragmatic about the challenges it

would face. The best way of seeing this

is for me to translate the segment on “Gosh” in full, in the hope that some of

Stutchkoff’s inherent cheekiness and conversational wit come through: [2]

A Jewish Woman from the Bronx pours her bitter heart

out to me: ‘I have,’ she writes, ‘a little boy who goes to a Jewish school and

studies very hard, but it is becoming very difficult to persuade him that he

should speak Yiddish at home. What does

he claim? That it’s too difficult for

him. Recently I shouted at him: “You

should listen to me, every minute with your “Gee” and with your “Gosh”!” He raised up to me a pair of innocent eyes and

said, “How do you say “Gee” and “Gosh” in Yiddish?” I didn’t know how to answer him. Truly, can you help me, Mr. Stutchkoff? I have told him that I will ask you.’

I can help you. I can tell you how Jewish children in the old

country used to express their surprise when they didn’t know “Gee” or “Gosh”,

but they spoke Yiddish and so their sayings sounded right. Perhaps they wanted to fit in with the other

little Jewish boys, I don’t know. When a

little Jewish boy felt really surprised, he used to shout: “OY! Mamelekh!

Tatelekh!” or (in Lithuania): “Maminke! Tatinke!”.

Or he used to say: “Really?! What are

you talking about? Ze! Ova! Oy-oy-oy!” And

so, he would fit in with all the other little boys.

In

that one response, Stutchkoff highlights not just the fact that there is rarely

only one way to translate any word into Yiddish, but also acknowledges that for

the next generation of American Jews, Yiddish was always going to play second

fiddle to English. However, thanks to

his epic efforts to capture the Yiddish he knew as a living, breathing

language, those of us in the generations that followed can still experience

Yiddish in all its messy, non-standardized glory. Despite his understandable fears for Yiddish’s

future, Stutchkoff created some of the best resources for ensuring its

continuing survival not only as a point of historical or literary interest, but

also as a language of gossipy backchat. In

Stutchkoff’s view of Yiddish, bedspreads and window blinds are just as relevant

as matzo and gefilte fish to American Jewish life. Thanks to him, I can write Yiddish limericks

and understand phrases that no longer appear in any modern Yiddish dictionary. If he were still alive I’d buy him a pint, but

in lieu of that I’ll just have to say, װאָס אַ מענטש.

[1] No surprise that the Yiddish word for “dunking” is “tunken”.

[2] The initial paragraph is the listener’s letter, while the section in bold is

Stutchkoff’s response, or as close as I can render it. Even with eight dictionaries, there are words

here that I can’t find.

No comments:

Post a Comment